On July 17, 1944, before the unveiling of the first atom bombs, a horrendous explosion happened 30 miles north of San Francisco, a mile away from the town of Port Chicago, California. The explosion vaporized one navy ship and destroyed another and killed 320 men who were tasked with loading munitions onto the two ships. Much speculation has taken place in the more than seventy years since it happened, and there is still no official cause for the disaster, World War II's worst home-front disaster.

Feature Article

The 1944 Disaster at Port Chicago

The Naval Ammunition Depot at Port Chicago, California

was one of the main hubs of ammunition during World

War II for the Pacific Theater.

It is located 30 miles northeast of San

Francisco close to Mare Island in Vallejo,

California. The town, which is approximately a mile from the

munitions depot, had a population of about 1,500. The site was used as a

shipyard during World

War I, and became a depot shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

In 1942, the military service in the United

States was still segregated, and in the Navy, black sailors were not

involved in sea duty. During that time, there were approximately 1,400

black enlisted men, 71 white officers, 106 marines who were serving as

guards, and 230 civilian employees at Port Chicago. The main job of the

enlisted men was to unload ammunition from the railroad

boxcars which brought them to Port Chicago and load them into a hatch via

cargo nets. The ammunition was said to include incendiary bombs, depth

charges, small caliber bullets, and large bombs which weighed up to a ton.

This loading went on 24 hours a day, and was done by men who had no

special training

in handling ammunition. There was widespread concern about the safety

of the men, but they were told by their commanding officers that the

munitions were not active and would not explode.

On July 17, 1944, there were two ships being loaded at the port, the SS

E.A. Bryan, which was packed with 4,600 tons of explosives and ammo, and

the SS Quinault Victory, which the men were in the process of loading 430

tons of bombs. There were 98 enlisted black men, 13 naval guards, and 31

merchant marine crewmen working on the Bryan and 100 black men, 36

crewmen, and 17 naval armed guard working on the Quinault Victory.

At 10:18 that night, an explosion was heard up to 200 miles away. An Air

Force plane flew over Port Chicago, at about 9,000 feet. They

reported that they saw pieces of white hot metal, some as big as a house,

fly straight up in front of them. The co-pilot described it as "a

fireworks display" which lasted approximately a minute.

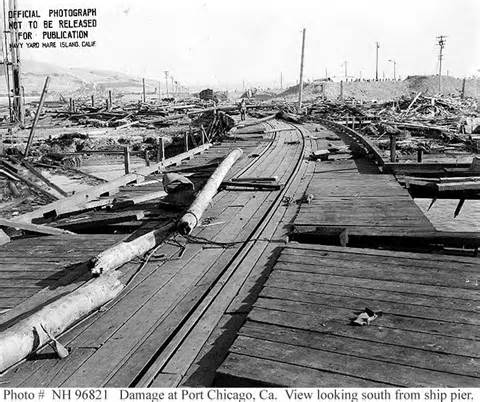

The SS E.A. Bryan was vaporized, and 320 men on the pier with it were

killed instantly. Not a single identifiable piece of the ship was ever

found. Only 51 bodies could be identified, and some of them were found

more than a mile away from the pier. 202 of the dead and 233 injured were

African-Americans, and this one incident was 15% of all African-American

naval casualties in the entire war.

The stern of the SS Quinault Victory was moved more than 500 yards from

where it sat before the explosion. The rest of the vessel was in pieces,

the ship having been lifted out of the water entirely.

The Napa Journal reported the next day, "The hills of the Napa Valley were

momentarily illuminated by sunlight."

The St. Helena Star quoted an eye witness who happened to be standing in

front of him home. The witness, Tom Street, was quoted as saying, "First

there was a sudden mushroom of white light, followed an instant later by

another, then a few moments later the intense roar and the concussion of

the blast."

Clocks

in the town of Port Chicago, more than a mile away, were stopped at 10:19,

and not a single building in town was undamaged. The Richter scale

registered as 3.5 in Bonner's Ferry, Nevada.

Strangely, the head of Port Chicago, Captain William J. Parsons, who had

been stationed at Los

Alamos Laboratories before being transferred to Port Chicago just

before the disaster was promoted to commodore directly following the

disaster. He went on to direct the tests in the Pacific, including the

Bikini test. He was instrumental in designing and implementing the first

atom bomb, working directly under Dr. Oppenheimer. He was also the bombing

officer on board the Enola Gay when it dropped the atom

bomb on Hiroshima.

A month later, hundreds of enlisted men, including several injured in the

explosion, refused to load ammunition due to the fact that nothing about

the handling of the bombs had changed. More than 200 of them were

convicted of disobeying orders in a summary court martial. Each of them

forfeited his pay for three months, and several of them were witnesses in

the mutiny trials which would happen shortly. The rest of them were

shipped to various places in the Pacific Theater, where they were assigned

menial jobs like cleaning latrines and picking up cigarette butts and

garbage. Upon their return stateside, they were each given bad conduct

discharges and denied all veterans'

benefits.

Fifty of them were tried for mutiny, which carries a maximum punishment

of death. In their courts martial, they indicated that they had not

been ordered to load the ammo, but were simply asked if they wanted

to load ammunition.

All 50 of them were found guilty of mutiny and sentenced to 15 years. In

1946, forty-seven of the prisoners were released from prison but were made

to remain in the Navy on probation. They were all sent to the South

Pacific and slowly, a few at a time, were dishonorably discharged.

Port Chicago is no longer in existence, having been expanded and renamed

the Concord Naval Weapons Station.

The explosion was looked into in depth by a team from the Manhattan

Project, and given eye witness reports such as those describing a "ball of

fire mushroom" and "...that literally filled the sky with flame," it was

thought that the explosion may have been caused by a nuclear

bomb, specifically a low-yield atomic bomb. That idea still exists today.

It is backed up by numerous facts, garnered from different places.

Documents from Los Alamos indicate that at the time of the Port Chicago

detonation, scientists embraced what was then called the Hydrodynamic

Theory of Surface Explosion, which posited that the only potential

delivery device for an atomic bomb was a ship, which would have to be

detonated in a harbor.

The navy photographed

the entire explosion from across the bay, and records of the contents of

the box cars which were being unloaded at the pier and loaded onto the

ships is missing. Records for all other cars on the train were intact.

Theorists believe that the 9000-pound Mark II atom bomb may have been in

one of those two cars.

Contra Costa County and surrounding towns and counties including Alameda,

Santa

Clara, and San

Mateo have had abnormally high cancer

rates since the mid-1940s, though those rates have dropped in the past few

years.

Still, more than 70 years after the event, what actually happened to cause

the detonation of whatever it was which caused this disaster is anybody's

guess.

Recommended Resources

Dissects the events which resulted in the vaporization of one ship, the demolition of another, the deaths of 320 men, and the mushroom cloud which indicated to many that this was the first nuclear blast in history.

http://dmc.members.sonic.net/sentinel/usa5.html

Munition Ships Explode in San Francisco

Contains a video news reel of the explosion at Port Chicago, along with the news which puts it in context.

http://www.britishpathe.com/video/munition-ships-explode-in-san-francisco/query/ports

Navy History: Naval Magazine, Port Chicago

Displays photographs and descriptions of the disaster and the resultant damage. Also links to a Frequently Asked Questions section specifically about that disaster.

http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/pl-usa/pl-ca/pt-chgo.htm

Shares information about the worst World War II-era disaster in the homeland, including photographs, background about the segregated military, an explanation why the vast majority of those who were killed were African-American, and a list of the dead, their positions in the Navy, hometowns, and ages when known.

http://www.usmm.org/portchicago.html

Chronicles the 1944 explosion which took place in San Francisco Bay and presents the evidence which the author says points to that explosion being the first nuclear bomb, accidentally detonated at the Navy dock at Port Chicago.

http://dmc.members.sonic.net/sentinel/usa4.html

The Last Wave from Port Chicago

Provides the results of the author's investigation, lasting more than twenty years, of the 1944 explosion at the Port Chicago Naval Magazine. This site covers the entire history of the explosion and also documents the connections between this tragedy and the Manhattan Project and Los Alamos, where the atom bomb was being assembled.

http://www.petervogel.us