Voodoo (Voudou) might refer to Brazilian Vodum, Candomblé Jejé, Tambor de Mina, Cuban Vodú, Dominican Vodú, Haitian Vodou, Louisiana Voodoo, or West African Vodun.

Spelled a variety of ways, Voodoo is a generic name for the religious traditions of the West African kingdom of Dahomey that flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries, and is now known as Benin.

Large numbers of people from Dahomey were sold into the slave trade, and transported by Spanish slave traders to Haiti and other parts of the West Indies.

Spanish missionaries established Catholicism early in the settlement of Haiti but, unlike most of the other islands in the West Indies, Catholic missionaries did not remain in Haiti. It wasn't until 1860 that the Pope granted Haiti an all-French clergy, as French culture and language were dominant on the island. Today, most of the Haitian people profess to be Roman Catholic, but many of them also practice Voodoo.

The long absence of Catholic clergy in Haiti allowed for a different development of religion among the African people there. Uninhibited, the slaves combined their native Voodoo religion with Roman Catholicism. Rather than strict monotheism, the result was a syncretistic polytheism, with the triune God of Christianity as the supreme deity (loa) in a pantheon of African deities, which extended beyond those of the Dahomey kingdom to include deities from other parts of West Africa, as well as deified ancestors, and Catholic saints.

As people from several West African tribes were enslaved on Haiti, several tribes contributed to the gods who are recognized in Voodoo, including the Angoles, Caplaous, Congos, Dahomeans, Ethiopians, Fons, Haoussars, Ibos, Libyans, Malgaches, Mandinges, Mondongues, and the Senegalese. The names of these tribes serve to designate separate Voodoo rites, although most of them are fundamentally related to the other rites, although they may appear superficially different.

Because Africans from different tribes were sold into slavery together, they had to combine their separate rites or be isolated in the place where the slave trade took them.

In Voodoo, there is no organizational hierarchy. Each Voodoo temple (hounfour, oum'phor, oufo) is independent, although following the tradition of Voodoo but modifying or changing the ceremonies and rituals in various ways. This is because the religious leaders (houngans) are believed to speak directly to the gods of Voodoo, and are not answerable to anyone else.

Each temple has two structures, one for the religious leaders and another for the lay members. The chief religious leader of each temple is viewed as royalty. If a man, the emperor of the temple is known as a houngan. If a woman, the empress is a mambo. The symbol of office is the calabash rattle (asson). There are several other roles in the organizational structure of the temple, each serving different functions. The local Voodoo Society serves as a social annex to the temple and has officers with titles like those of a national government, including a president, ministers, senators, deputies, generals, secretary of state, and district and local commanders.

Like Ifá, African tradition holds that Voodoo had its origins in the legendary city of Ilé-Ifẹ̀, which is viewed much like an African Mecca. Ifẹ̀ is the fatherland of the Voodoo gods. However, the African origins of the Voodoo gods are complex. Although Papa Legba, the origin and male prototype of Voodoo, unquestionably comes from Ifẹ̀, the whole of the Voodoo pantheon of gods do not come from the same place. The Voodoo gods come from several places in Africa, as well as Judea.

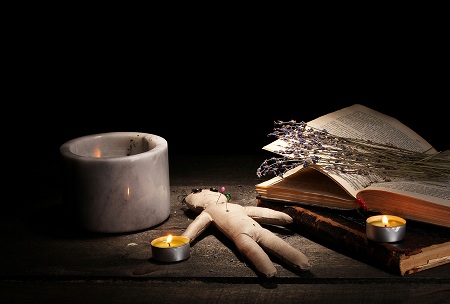

Through various Voodoo rituals, the gods (loas, mysteres, or voudon) are summoned by the houngan or mambo. Summoned gods may enter a pottery jar (govi) or they might become incarnate by "mounting" a Voodoo follower. The mounted follower (horse) loses all consciousness, and is wholly taken over by the mystere, who might prophesy, dance, or perform magic, all without mounted person having any awareness of it.

The musical instruments, chants, dances, and prayers that are a central part of Voodoo each have symbolic interrelationships that are important to the understanding of the religion.

There are a large number of Voodoo traditions. In the larger cities of Haiti, such as Port-au-Prince, Voodoo artifacts are a source of revenue, but far removed from the tourist stops, Voodoo magic, rituals, and ceremonies are as popular today as they were centuries ago.

The focus of this category is on Voodoo, by whatever name it might be known, and in whatever tradition it might be practiced.

Feature Article

The Origins of Voodoo in the Caribbean

Americans, at least in the United

States, tend to blur the several events that eventually led to the European

colonization of North

America, associating Christopher Columbus with the landing at Plymouth

Rock in 1620, despite the fact that Columbus died in 1506, and that

he never set foot on any part of what was to become the United States.

The four voyages to the New World that Columbus made, between 1492 and

1502, were to what is now known as the Caribbean,

particularly the Dominican

Republic, Haiti,

and Cuba.

The islands of the Caribbean were Europe's first colonies in the New

World, and Spain

was virtually unchallenged in its control over the region for more than a

century. Toward the end of the sixteenth century, England,

France,

Portugal,

the Netherlands,

and Denmark

were vying for a piece of the West Indies.

The economy of the Caribbean quickly centered on the production of sugar

cane. As international trade grew up around the plantations of the

Caribbean, the region soon became the destination for thousands of African

slaves, who did the actual work, becoming the most significant ingredient

in the success of plantation society.

The first African

slaves arrived shortly after the Europeans, and the islands of the

Caribbean was among the last areas to abolish the practice, for nearly

four centuries of slavery.

Upon their arrival, the Africans not only had to deal with their positions

as slaves, but they had to adapt to new languages and cultures, even among

one another, since the slave traders didn't differentiate between families

and tribes. Their strategies of accommodation and resistance resulted in

the syncretic religions of the Caribbean that are known as Caribbean

Voodoo, Santeria,

and other Creole religions.

More than half of the five million Africans who were transported to the

Americas ended up on the sugar plantations of the Caribbean. The English

territories of Antigua,

Barbados,

and Suriname

received the most slaves during the mid-1600s but, by 1750, Jamaica

had surpassed Antigua and Barbados in the production of sugar, a position

that was lost to the French colony of Saint

Domingue by 1780. Cuba later became dominant, but only after the

Haitian Revolution brought an end to sugar production in Saint Domingue.

The importation of slaves within the Caribbean was dictated by the

changing patterns of sugar production, with the largest numbers of slaves

going to wherever sugar production was highest. This fact was the cause of

the cultural exchange that brought about the development of the Creole

religions.

The religion of West Africa, where most of the slaves were taken from, was

Vodun, but just as there are sharply differing beliefs and practices

within the Christian religions today, there were several variants of Vodun

in West Africa, as practiced by the several different tribes.

The religious rituals of the various West African tribes were commingled

and modified as a result of slavery. When a group of Africans from three

different tribes were thrown together, they either had to combine their

separate rites or the differences would isolate them in an environment

that was already unfamiliar and hostile. As a result, different religious

groups were forced to more or less combine their religious beliefs,

creating a new Voodoo rite that was not pure.

Some tribes were able to either regroup and preserve their rites intact,

or maintain the purity of their rites even while living among other

tribes. Slaves who were transported to Haiti were more likely to retain

their rites because the larger concentration of slaves in Haiti allowed

for larger numbers of people from the same tribes. However, even in Haiti,

the practice of Voodoo was more likely to be syncretic in nature.

Further change in the religious practices of the West Africans who came to

the Caribbean as slaves was forced upon them by European slaveholders. In

the early days of slavery in the Caribbean, the Voodoo priests were able

to carry on their profession without attracting too much attention. In

time, however, the sounds of the drums, the possessions, or mystical

seizures that occurred in the slave huts attracted the attention of the

slave masters.

The practice of Voodoo frightened the Europeans, and was seen by the

authorities as a threat to the stability of the plantations. It was

outlawed in most of the British Caribbean islands in the early 1700s.

Slaves found in possession of any symbol of Voodoo were punished cruelly,

even killed.

Rather than bringing a halt to the practice of Voodoo, repression simply

forced it underground, changing it in the process. The art of making

sculptures in clay or wood, highly integrated in other black cultures, was

lost in Haiti.

In 1791, the Haitian slaves, numbering nearly 500,000, rebelled against

their masters, who were a clear minority, beginning a long process that

became known as the Haitian Revolution, which eventually led to the first

independent republic in the Caribbean. Like other rebellions in the

British West Indies, the Haitian Revolution was centered in the practice

of Voodoo, which were marked by a pact between the revolutionary leaders

and the Voodoo loas or spirits.

Winning their independence, the former slaves laid Haiti to waste,

destroying the economic structure of the islands and severing their

connection to the international markets, which they had supplied with

sugar, coffee, and cacao.

This opened opportunities for Cuban sugar producers. Haitian plantation

owners who survived the violence fled to Cuba, bringing their skill,

experience, and contacts in the sugar and coffee production industries,

increasing the demand for slaves in Cuba.

Between 1512 and 1761, about 60,000 slaves were imported into Cuba, a

number that rose to 400,000 by 1838, the majority of whom worked under

awful conditions in the sugar, coffee, or tobacco fields. Cuba remained a

slave

society until 1886, two years prior to its abolition in Brazil.

Not only were the religious practices of West Africans syncretized as a

result of the commingling of various tribes after their arrival in the

Caribbean, but Catholicism

also had its influences, which can be seen in the practice of Voodoo

today.

Following the Haitian Revolution, Jean-Jaques Dessalines declared himself

to be the head of the Catholic Church in Haiti. As a revolutionary, he had

himself caused the assassination of large numbers of Catholic missionaries

by his failure to prevent the slaughter of white colonists. In response, Rome

refused to send priests into the country. As a result, the principles of

Voodoo and Catholicism were merged, and Catholicism was declared the

official religion of Haiti.

Haiti also ordained Haitians as Catholic priests, a step that was not

legitimized by the Vatican,

but the mingling of the two religions shaped the Haitian Voodoo rituals in

an interesting way, one that continues today, not only in Haiti but in Mexico

and parts of the United States where there are large Hispanic populations.

Haitians attended Catholic services, and used the rituals of Catholicism

to mask their continued practice of Voodoo. In many respects, Catholicism

serves as the public front for the secret practice of Voodoo.

Recommended Resources

Jahari is a high priest of Kongo Voodoo, capable of helping people in distress, whether it be over relationships, financial troubles, or other needs. His services include love spells to promote harmonious relationships, passion spells, and spells for money and success, and for luck in romance, family and friends, gambling, lottery, bingo, gaming tables, and casinos as well as for for happiness, the end of loneliness, and last chances. Voodoo hexes are also possible through Jahari.

https://kongovoodoo.com/

Dedicated to the practice of Haitian Vodou, the temple is based in Quebec. Its religious leaders are introduced, and an overview of its Initiation, Rentre Kanzo, Zin, Lever Kanzo, and Baptem rituals are discussed, along with the Rada, Nago, Petro, and Gede spirits. Available services are defined and may be purchased online. Other resources include an online store offering a variety of services and products, a gallery of photographs, and a blog.

http://www.labelledeesse.com/

Marie Laveau's House of Voodoo

Situated in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana, the Voodoo shop offers a wide variety of items used in the practice and learning of spiritual and religious ceremonies, such as tribal masks, statues, talismans, and charms, as well as a selection of psychic and spiritual readings, which are available everyday from noon until closing time. Other products include tee shirts, jewelry, and books. Schedules, and ordering and shipping information are included.

https://voodooneworleans.com/

Serving as a means of disseminating information about the beliefs and practices of the voodoo religion in New Orleans, Louisiana, the site features information, products, and services in the tradition of Louisiana Voodoo, including spells, arts, specialty rituals, and historical data. Other resources include biographies of prominent people, schedules and policies for historical voodoo tours are included, with testimonials and contacts..

http://www.neworleansvoodoocrossroads.com/

Registered as a church, operating in southeastern Pennsylvania, Sosyete du Marche is led by Mambo Vye Zo Komdande LaMenfo, the author of several books on the subject of Voodoo and related topics, who practices Haitian Voodoo. Her books are highlighted, and information about voodoo as it is practiced in the United States is offered, including text articles, a list of services, products available for purchase online, schedules, and terms.

http://www.sosyetedumarche.com/

Aimiwu, a High Priest of Voodoo, offers spells for love, impotence, pregnancy, revenge, protection, divorce, and wealth, as well as those involving witchcraft, voodoo dolls, black magic, ghosts and spirits, and African Voodoo. Details of each of his services are provided, including hours, contact information, and testimonials from clients. General information about Voodoo and related topics are also provided.

https://www.afrikanvoodoopriest.com/

Maintained by Houngan Hector, a high priest (Houngan Asogwe) of the Haitian Vodou religion, the site includes his biography, an overview of Haitian and Dominican Vodou, its rituals and ceremonies, the Lwa (spirits of Vodou), and free Haitian Vodou lessons that include a step-by-step guide to the faith and practice, its terminology, beliefs, spirits, lineages, ranks, rituals, and ceremonies, and other data, which is available online. A discussion of homosexuality in Vodou is included.

http://vodoureligion.com/

Located on the French Quarter, the Voodoo Authentica of New Orleans Cultural Center and Collection is owned and operated by a voodoo practitioner, and features a line of locally produced voodoo dolls, gris gris bags, potion oils, and other spiritual arts and crafts, which may be purchased online. Ordering information and customer comments are included, and its conventions and special events planning services are presented. A glossary of terms is also published to the site.

http://www.voodooshop.com/

Established in 1990, the work of the temple focuses on traditional West African spiritual and herbal healing practices in New Orleans, Louisiana. An overview of Louisiana Voodoo is presented, as well as an introduction to the local facilities, its cultural centers, and services. Other resources include a calendar of events and an online shopping area offering oils, sachets, CDs, books, incense, and other products.

http://www.voodoospiritualtemple.org/